The world’s most popular psychoactive drug is something you and 80% of Americans enjoyed today. And you’ve probably been told that it’s not so good for you. The French Revolution is believed to have been planned by the intelligentsia in coffee houses – Mecca banned it in the 1500s. But is coffee really all bad?

There’s some truth to the claim. In certain doses and at certain times of the day, caffeine (which is the culprit in coffee) can impact your sleep, nervous system, and HpA axis, causing that jittery wired-but-tired sensation.

To understand whether or not coffee is actually “bad” for you, we need to explore what it does inside our bodies.

During the day, our brain produces a chemical called adenosine, which naturally binds to the accompanying receptors our brain creates. As our brain creates the adenosine and it binds to these receptors, we become drowsy, fatigued, and a bit less focused. Sound familiar?

Adenosine is incredibly important. It helps to balance our other hormones, including stress-induced cortisol and adrenaline. And during our nightly rest (of hopefully 8 or 9 hours!), our adenosine supply and receptors reset, leaving us fresh and vibrant when we wake with a natural alertness from increased cortisol supply.

The problem lies in the fact that adenosine and caffeine are incredibly similar, molecularly speaking. As a result, when we start the day with caffeine, our brains naturally-produced adenosine must battle with caffeine molecules for the receptor slots. This process tricks our brain into thinking it’s alert, which is good — sometimes. Unfortunately, all that adenosine has nowhere to go, increasing our fatigue. Simultaneously, our body begins to rely on caffeine, causing us to want more of it. Yet our brain also produces more adenosine to counteract the stimulation, and more adenosine receptors to house the existing adenosine stores.

As this continues repeatedly, it leads to reduced production of norepinephrine, which gives us our natural “spunk” in the morning. As it’s reduced, it reduces neuronal communication, leading to brain fog.

None of that is to say we shouldn’t have coffee.

If you can hold off on that first sip for an hour (or 3!) after you wake up, you will give your central nervous system time to regulate. This short delay will help you to not feel overstimulated, yet still benefit from the improved focus and alertness you know and love.

But is this waiting period just making it a little less bad? Is coffee destined to remain our guilty pleasure, but our enemy nonetheless?

I’m happy to say that the answer is “no”!

In fact, a recent study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation suggests that your daily cuppa joe may actually have a positive epigenetic effect on your brain, which means that it could sustainably transform your grey matter in a good way!

Crazy right? As we’ve discussed, we know that coffee has an unquestionable role in modifying certain central nervous system functions. But in some contexts and in particular doses, those same neural interactions can translate to things like improved focus, alertness, and increased attentiveness to a task.

What’s more exciting is the possibility of increased synaptic plasticity, or malleability, in neuron-to-neuron communication, as well as indicated decreased cognitive decline and aging in those with a variety of neuropsychiatric diseases.

In other words, coffee can preserve your grey matter, cognition, and possibly your youth!

In fact, Borota and his colleagues, found in the 2014 study that if given caffeine post-study session, the subjects had enhanced consolidation of long-term memory. Similarly, bees – which consume caffeine occuring naturally in citrus and coffea plants – are more alert and focused thanks to caffeine’s adenosine receptor antagonist activity.

It was found that honeybees that consumed the natural levels of caffeine in these flowers were three times more likely to remember and locate floral scents, compared to the bees given sucrose alone. This, of course, yields not just improved cognitive function for the bees, but better sustainable reproductive success for plants as well.

But must we constantly consume caffeine to see measurable and long-lasting benefits?

Researchers David Blum and Anne-Laurence Boutillier think not! Over the course of two weeks, the team took a look at two cohorts of mice and ran their RNA sequence. of each group of mice, one that was to be treated with water, one to be treated with caffeine-infused water. The initial sequencing revealed no frank or statistically significant differences.

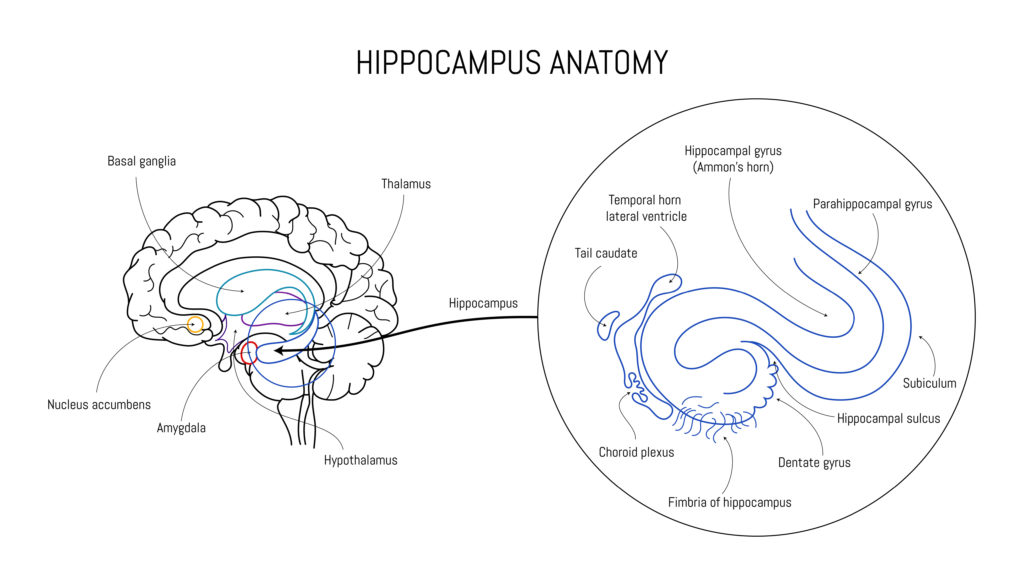

After giving one of the cohorts caffeine-infused water for two weeks, they looked again at the sequence, as well as at the molecules in their dorsal hippocampi — the memory center of their brain.

They found two very distinct genetic signatures, illustrating a clear modification in the cohort treated with caffeine. For reference, the control group expressed 209 modified genes in response to a learning session. The caffeine-treated mice expressed a five times greater response – a 47 down, and 162 unregulated in the water cohort, 419 down and 720 upregulated in the caffeine-treated cohort.

When looking at hippocampal matter of the cohort treated with caffeine, there was a clear epigenetic response specifically related to synaptic plasticity. In other words, there was an increase in communication from neuron to neuron, an improved ability for neurons to self-repair, and beneficial nervous system modification!

What’s even more fascinating is that even two weeks after the caffeine-treated cohort had received their last treatment, almost 30% of the patterns remained modified, illustrating that chronic caffeine consumption has a long-lasting effect on plasticity and genetic matter.

So what’s the moral here?

While we aren’t mice, there is clear promise that somewhere between 200 and 400 mg of caffeine daily could create long-lasting, positive effects on our plasticity, and may also have a beneficial effect on our cognitive function and memory.

It’s still a bit too early to know if this will have the same positive impact in humans, but hey, it can’t hurt to give it a try and enjoy that mid-morning or mid-day espresso!

Works Cited

Borota, Daniel, et al. “Post-Study Caffeine Administration Enhances Memory Consolidation in Humans.” Nature Neuroscience, vol. 17, no. 2, 2014, pp. 201–3, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24413697, 10.1038/nn.3623.

CRFS, McPhilimey BSc (Hons), MSc, MRes. “Exercise and Sleep Are Crucial to Our Metabolic Health – but We Ought to Mind Their Intertwined Relationship to Unlock True Wellbeing.” Themapsinstitute.com, 24 Aug. 2022, themapsinstitute.com/how-does-exercise-impact-sleep/. Accessed 30 Aug. 2022.

Paiva, Isabel, et al. “Caffeine Intake Exerts Dual Genome-Wide Effects on Hippocampal Metabolism and Learning-Dependent Transcription.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 132, no. 12, 15 June 2022, p. e149371, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35536645/, 10.1172/JCI149371.

—. “Caffeine Intake Exerts Dual Genome-Wide Effects on Hippocampal Metabolism and Learning-Dependent Transcription.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 132, no. 12, 15 June 2022, p. e149371, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35536645/, 10.1172/JCI149371.

Ribeiro, Joaquim A, and Ana M Sebastião. “Caffeine and Adenosine.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease : JAD, vol. 20 Suppl 1, no. 20, 2010, pp. S3-15, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20164566, 10.3233/JAD-2010-1379.

Rotondi, Jessica Pearce. “How Coffee Fueled Revolutions—and Changed History.” HISTORY, www.history.com/news/coffee-houses-revolutions#:~:text=The%20caf%C3%A9s%20of%20Paris%20sheltered. Accessed 30 Aug. 2022.

Wright, G. A., et al. “Caffeine in Floral Nectar Enhances a Pollinator’s Memory of Reward.” Science, vol. 339, no. 6124, 7 Mar. 2013, pp. 1202–1204, science.sciencemag.org/content/339/6124/1202, 10.1126/science.1228806.